There are widening gaps between pupils from poorer backgrounds and their classmates from better off homes since the post-Covid return to school in Wales.

Six key measures reveal the struggles to address this divide, which had been an issue already before the pandemic.

Last week brought the worst set of maths, science and reading results for 15-year-olds in the global Pisa tests

Here we look at this and other challenges.

How many pupils come from poorer economic backgrounds?

Whether a pupil is entitled to free school meals has been a long-standing measure of whether they come from a poorer economic background, based on the family being on low income or receiving benefits.

Around 95,000 pupils qualify for free school meals, about 20% of all pupils.

All children missed months of classroom teaching during Covid and on key measures, the impact can be seen clearly, but there are worries this is even bigger on those from low income families.

Here are the areas of concern:

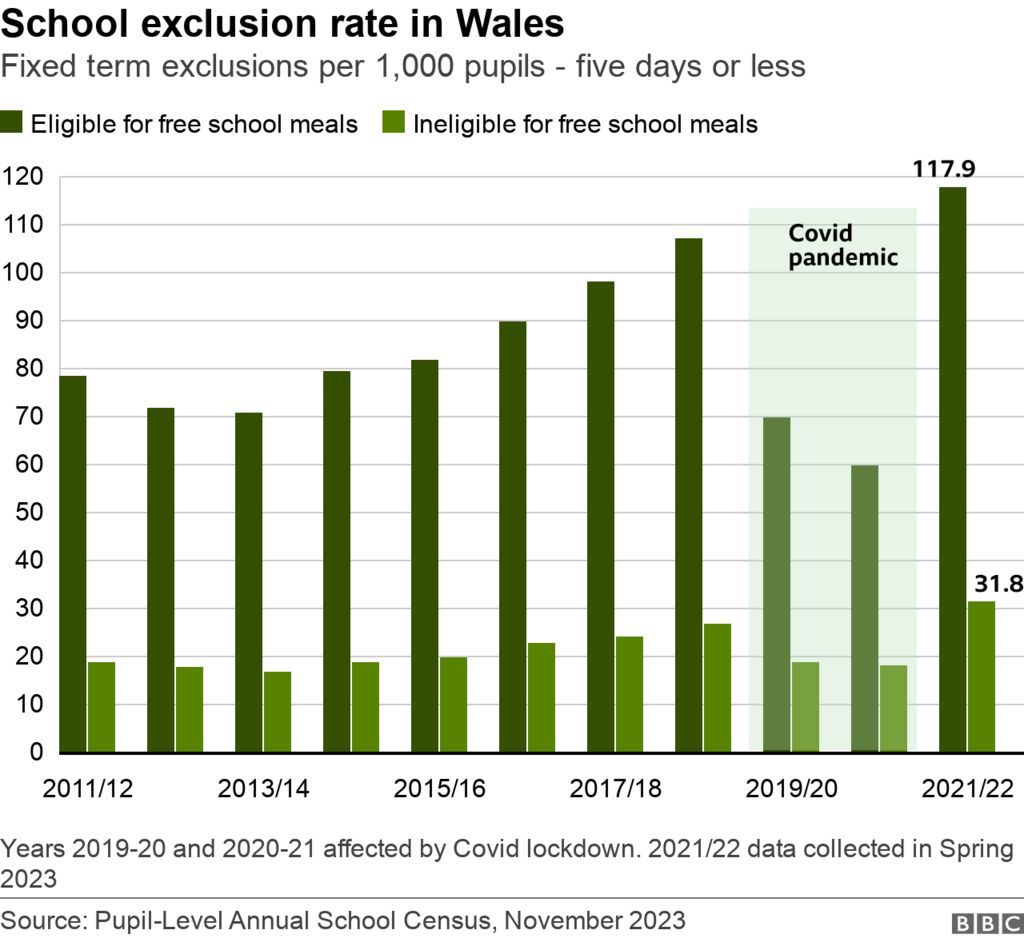

School exclusions

The number of permanent exclusions in 2022 was at a record high – more than 300 pupils.

But the rate of permanent exclusions was more than five times higher for pupils entitled to free school meals than those who weren’t eligible – 1.7 permanent exclusions per 1,000 pupils compared with 0.3.

These are still a rarity.

Fixed-term exclusions are more common – that’s five days or less, with the top reasons abusing or threatening a teacher and assaulting a fellow pupil. There were nearly 28,000 such short-term exclusions in the last year.

The exclusion rate for this is now nearly four times higher for those entitled to free school meals than those who are not.

The gap had been growing in the two years before the pandemic but now it’s the widest on record.

This comes at a time when exclusions for all secondary pupils has risen by 35% since the year before Covid.

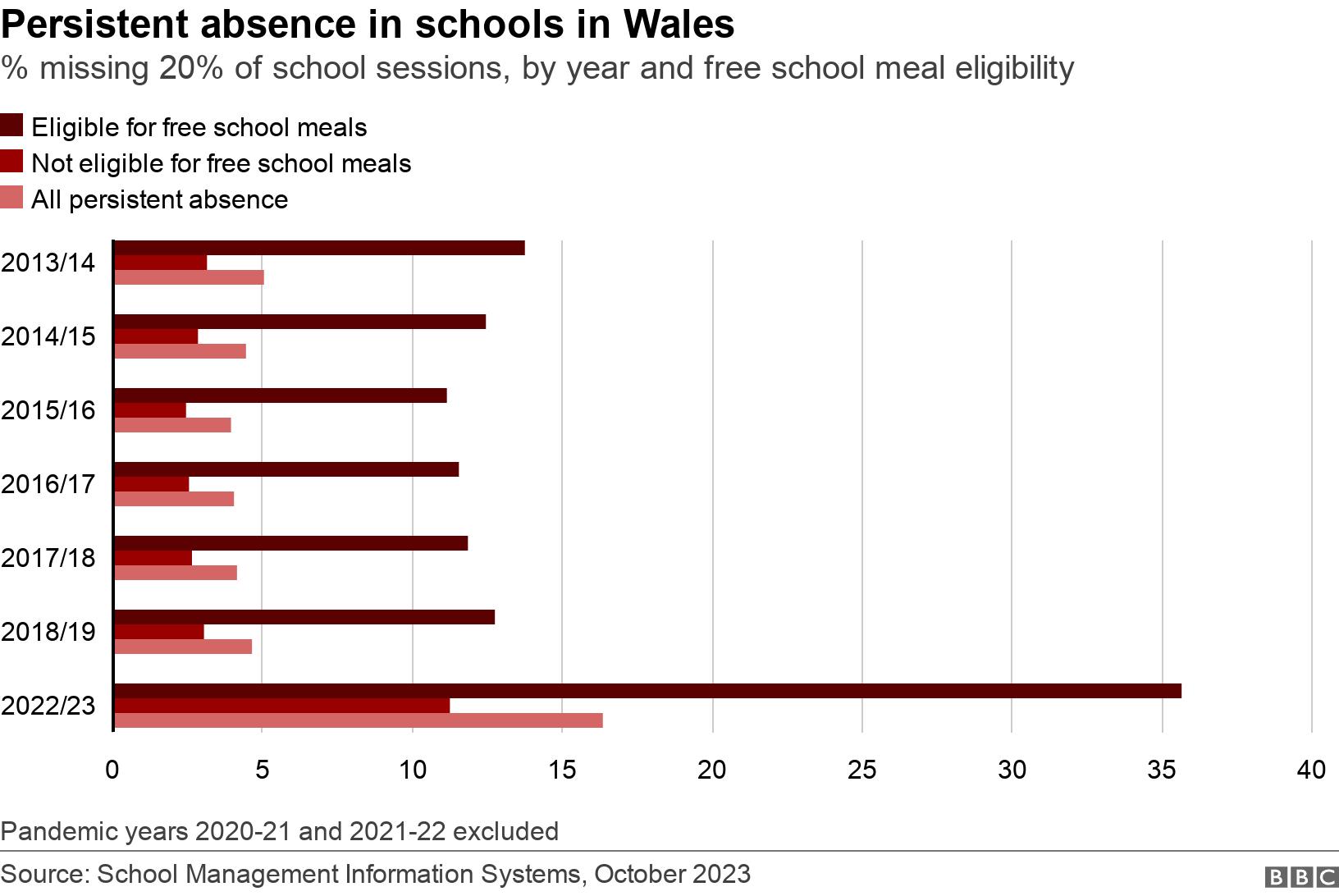

School absenteeism

School absenteeism – especially persistent absence – has got much worse since the pandemic.

Pupils have been judged to be persistently absent if they miss 20% of class time. So that is 60 half-day sessions a year.

But that threshold has now been changed to 10% – in a move designed to focus even more on improving attendance.

Education Minister Jeremy Miles said in a recent article: “Too many teachers tell me they are seeing challenging behaviour, worse attendance and lower levels of literacy and numeracy. We must not allow this to become the ‘new normal’.”

The figures we have for school absence are more up to date than the ones available for exclusions.

The percentage of secondary school pupils who were persistently absent has tripled to 16.3% from 2018-19 – the last full academic year before Covid – and 2022-23.

The figures also show that 35.6% of secondary school pupils eligible for free school meals were persistently absent in 2022-23, compared with 11.2% of those who did not qualify.

This is three times higher and an alarming widening of a gap which has now become a gulf.

It gets wider as secondary school pupils get older too.

The most recent figures so far this first term of the 2023-24 academic year – which includes primary school pupils – show 4.7% of students have met the persistent absence threshold of 10% of sessions missed, slightly down on the previous year.

But 10% of those eligible for free school meals are persistently absent (on the 10% threshold), compared with 2.7% of pupils not eligible.

The school inspection body Estyn said in its annual report: “Work to improve attendance has not led to a marked increase in attendance, especially that of pupils eligible for free school meals.”

The attendance rate for the academic year to date has been higher for pupils not eligible for free school meals (93%) than pupils who are eligible for free school meals (86.4%).

GCSE exam results – the attainment gap

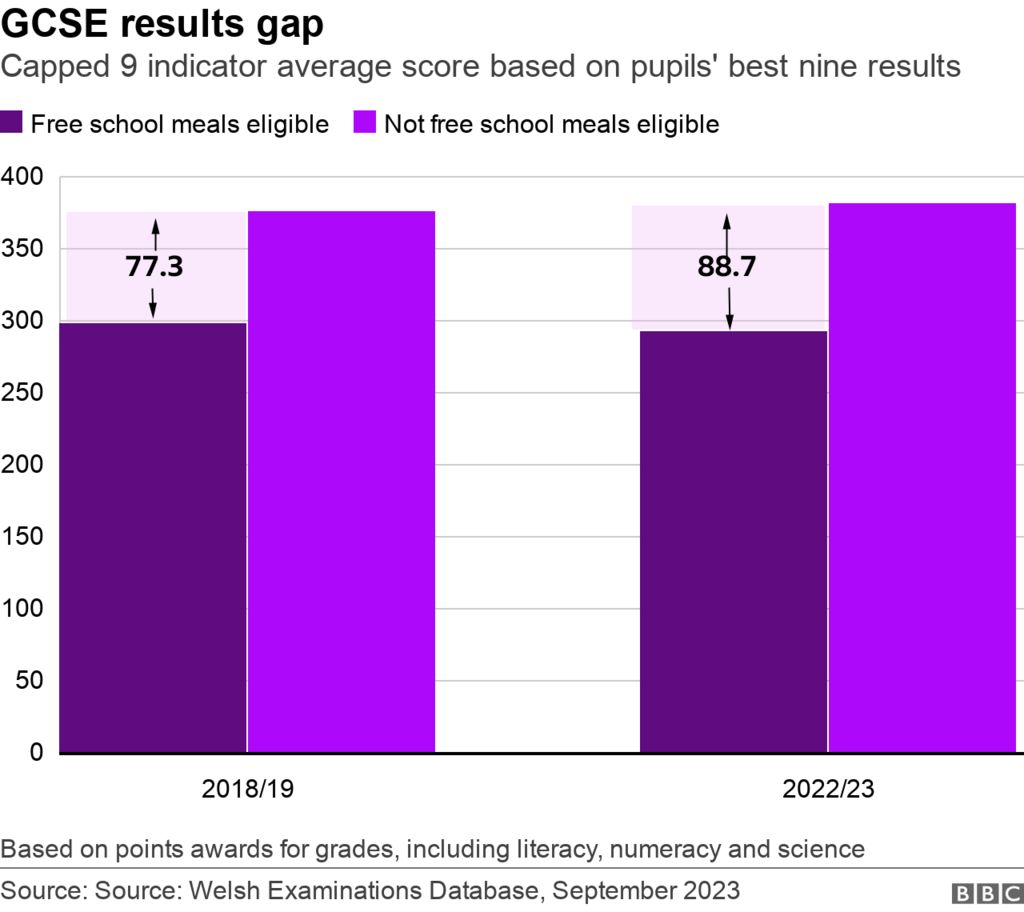

A widening gap can also be seen in terms of GCSE results.

Let’s look at two measures here.

Firstly, the so-called “Capped 9 indicator”. This looks at the grades in a pupil’s top nine subjects, including literacy, numeracy and science. Points are awarded, with an average points score overall at 365.5.

But the points gap between pupils sitting GCSEs who are eligible for free school meals and those who aren’t has widened from 77.3 before the pandemic to 88.7 in 2022-23.

The gap is widest in science subjects and narrowest in literacy.

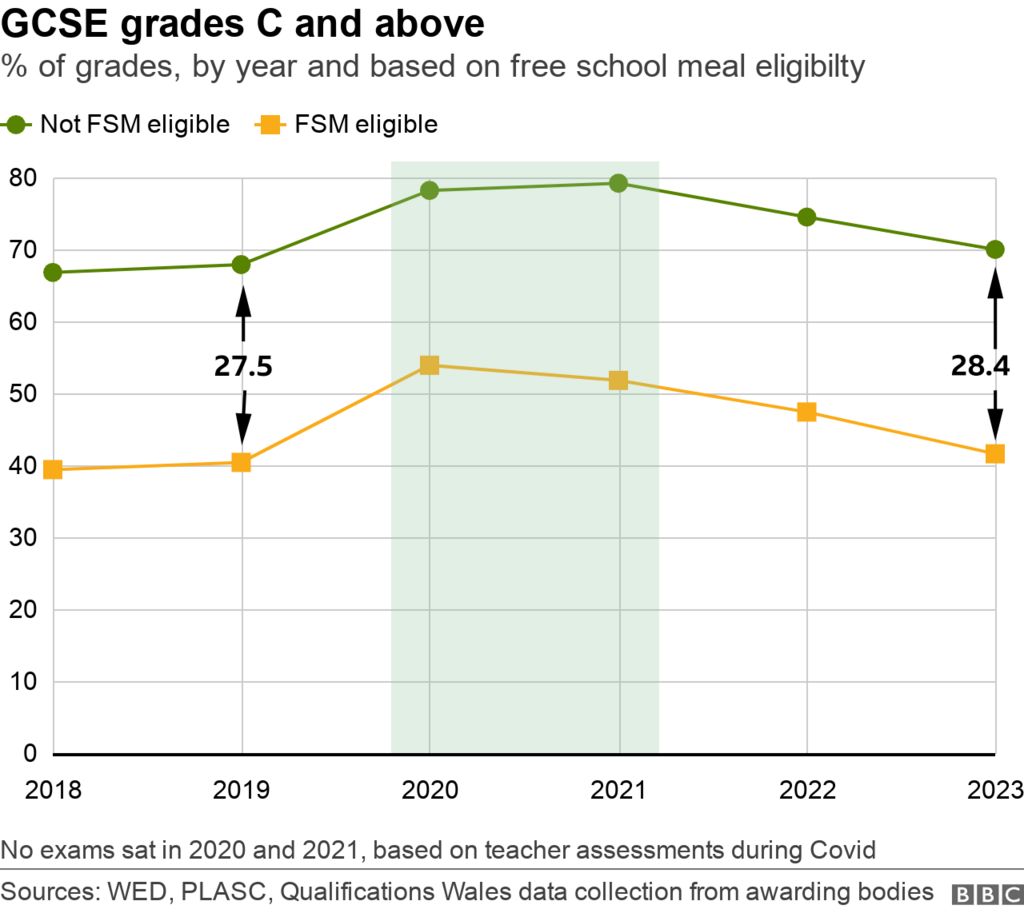

Next, when it comes to GCSE grades, Qualifications Wales figures show of pupils eligible for free school meals, 8.3% of grades were the top A and A*, compared to 24.1% of those not eligible. The gap has widened from 14 points before the pandemic to 15.7 in 2023.

For those not eligible for free school meals, 70% of the grades were C or above, compared to 41.6% of those who were eligible. That gap has also grown slightly since 2019.

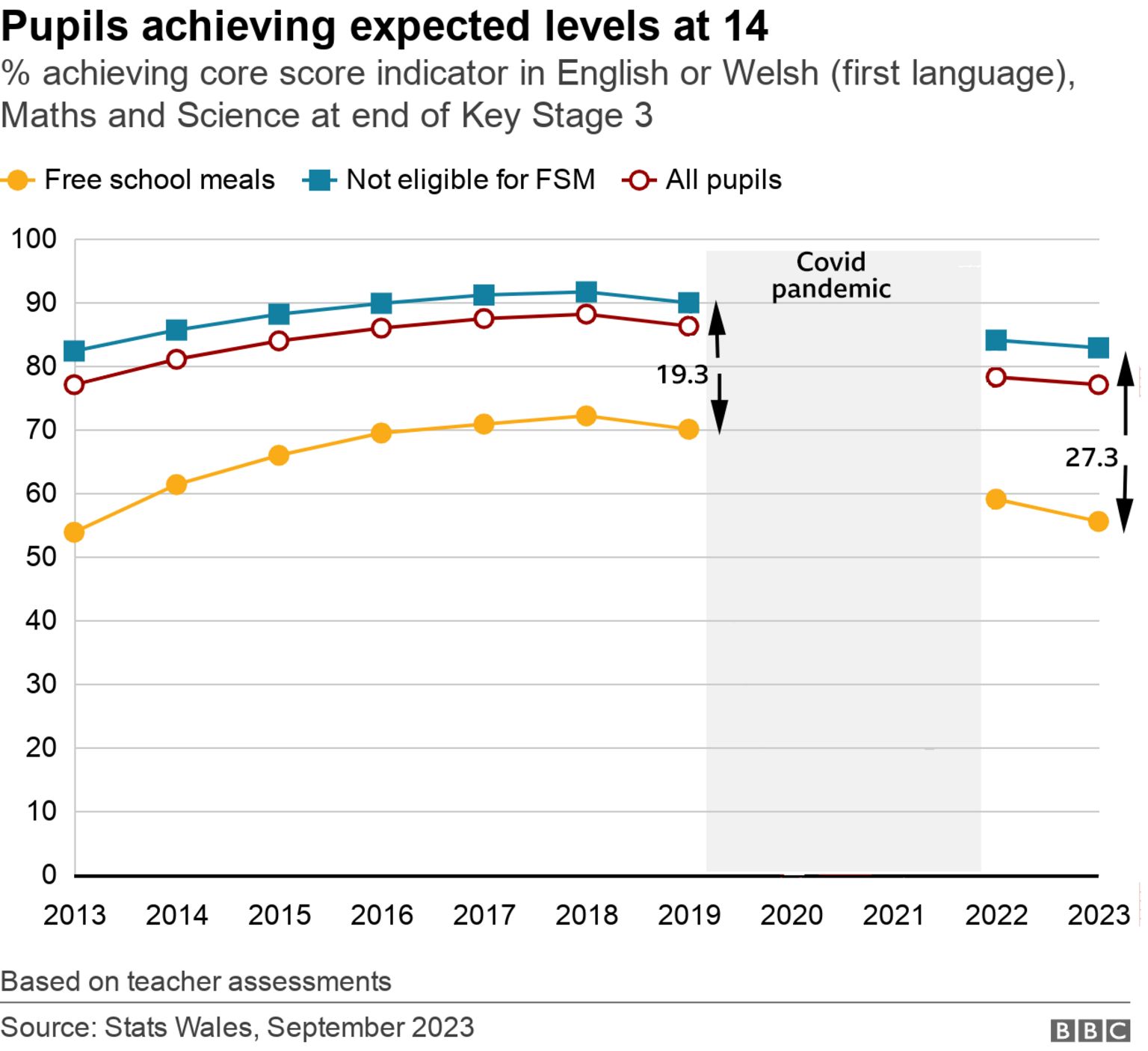

Pupils aged 14 in core subjects

When we look at pupils assessed in key subjects at the end of key stage 3 – aged 14 – then the gap is at its widest for 10 years.

Just over half (55%) of those eligible for free school meals achieved the core subject indicator – compared to 83% of those pupils not eligible.

The gap had been narrowing for most of the years before the pandemic.

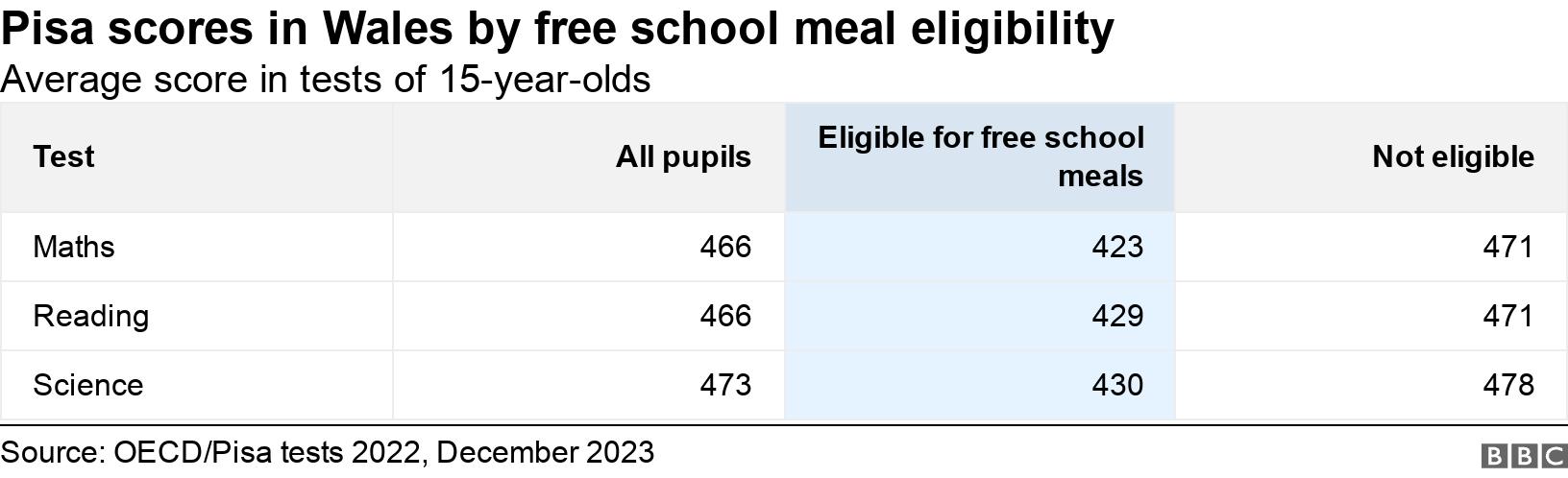

Pisa findings on 15-year-olds from poorer backgrounds

The new Pisa report for Wales found that there was more academic “resilience” than the international average – with more pupils from the poorest backgrounds ranking in the top performers in the maths, science and reading tests.

However, there were still gaps in performance between those from the poorer and richer socio-economic backgrounds.

When looking at free school meal status, on average learners eligible performed significantly lower in the maths test (average score 423) than learners not eligible (471).

Similar patterns were seen in reading (429 and 471) and science (430 for those eligible and 478 for those not eligible)

Apprenticeships – success rate gap widening

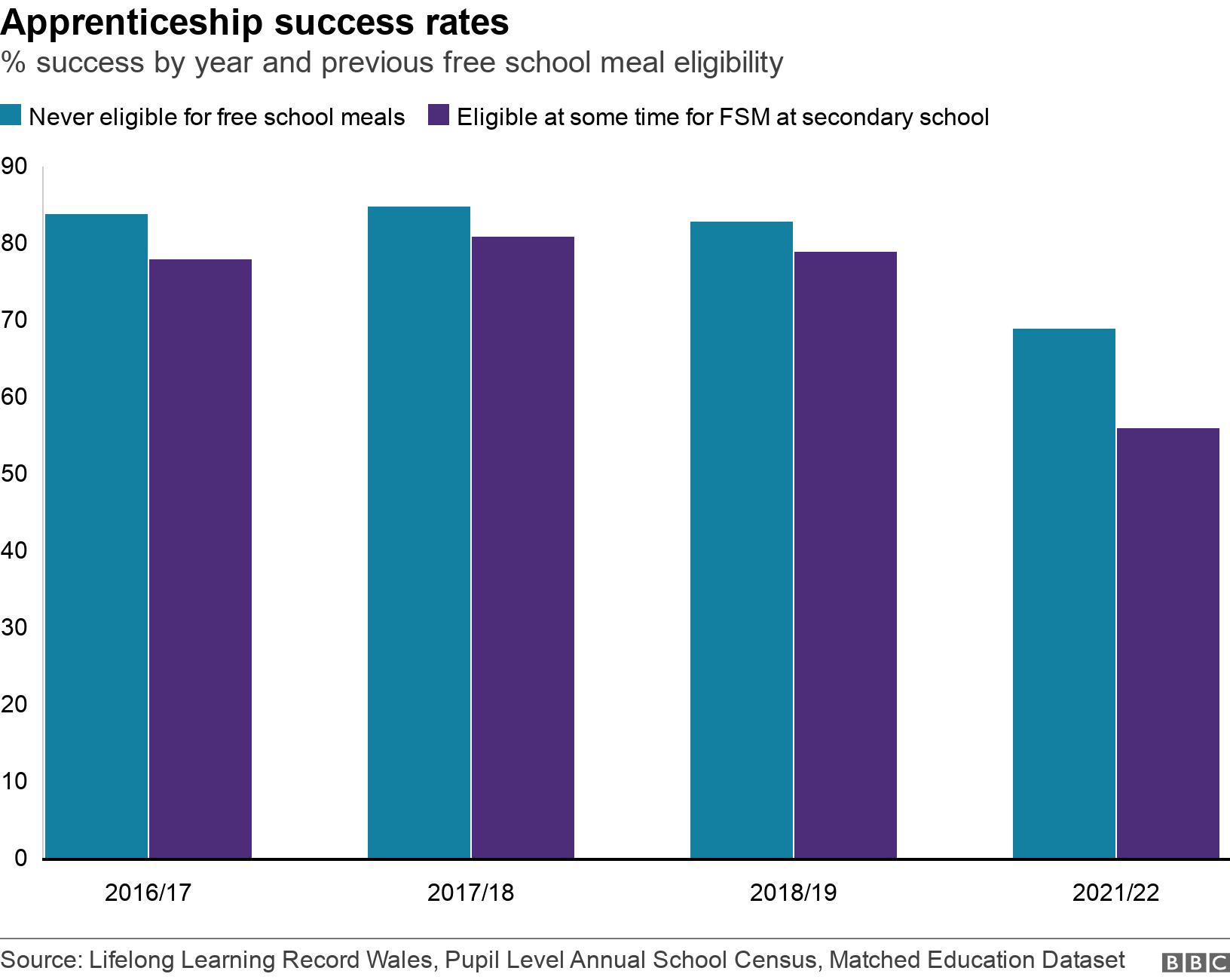

Figures also show similar issues around attainment involving apprentices from poorer backgrounds.

Recent figures have also looked at how more than 7,600 apprentices got on – and analysed this against their free school meal eligibility history for when they were in secondary school.

The report says: “Before the coronavirus pandemic, apprentices who had never been eligible for FSM had higher success rates than those who had been eligible, but the gap was narrowing.

“In 2021-22, the gap increased to more than three times the difference in 2018-19.”

The success rate fell post-Covid for all apprentices, but fell much more sharply for those who had been free school meal eligible.

Finola Wilson, a former English and maths teacher and director of Caerphilly-based education improvement organisation, Impact, said Covid had further disadvantaged the most vulnerable in society.

“Children who were already struggling to engage with and access school are now in a worse situation,” she said.

“Addressing the disadvantage gap is a societal problem. Each child’s situation will be different and will need an individual response. The first target should be to make sure all pupils are receiving an education, whether in school or via alternative provision.

“We also need to address the mental health crisis exacerbated by covid, which affects children and their parents and carers.”

Source : BBC